In this blog post I’ll continue describing my my visit to the NGO Wuqu’ Kawoq which is doing a lot of interesting things in rural Guatemala with regards to Maternal and Child Health!

As I was able to spend about a week at Wuku’ Kawoq, (an NGO working in Guatemala), with a half-day to visit the Mayan ruins at Iximche, I was able to see some of how Wuku’ Kawoq works with traditional midwives in Guatemala called comadronas.

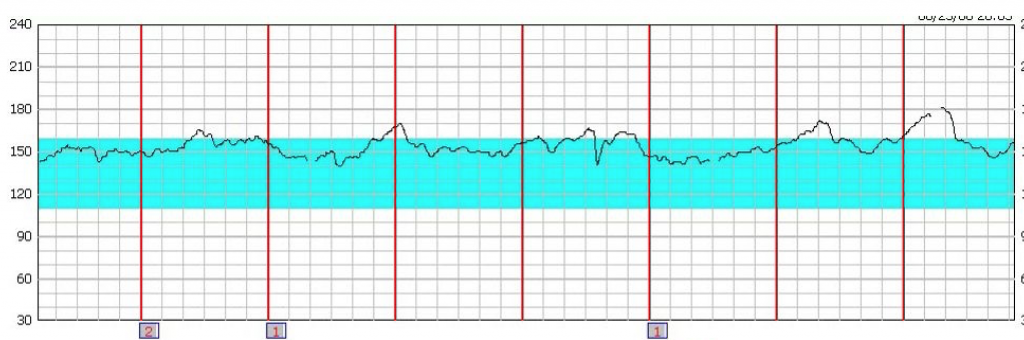

Interestingly, comadronas working with Wuku’ Kawoq can use a special cell phone, and attached fetal doppler sthethoscope, to record a fetus’s heart rate over twenty minutes. (Pictured above.) This information can be transmitted to Wuku’ Kawoq doctors to ascertain if the the fetal heart rate is too fast (tachycardia) or too slow (bradycardia), both of which might warrant further investigations, and also to determine that the fetus is still alive. In addition to average heart rate, the Wuku’ Kawoq doctors can also look for evidence of fetal heart variability, which has a specific number for how much the heart rate varies over time. If a fetus’s heart rate is responsive (and thus shows variability) to the changes in oxygen content, and other factors, in the blood is receives from the placenta, then this is a good sign which indicates that the fetal nervous system is responding appropriately. By calculating the time between each fetal heart beat, a fetal heart rhythm strip can be generated which depicts the changes in fetal heart rate that occur in fractions of a second.

Amazingly, the graph above the fetal heart rate is on the left side (normal fetal heart rate in blue), and time on the horizontal axis with each small box

being 10 seconds, and with 1 minute passing between the bolded vertical lines. (From http://www.ob-efm.com/fhm/files/quiz.php). Fetal heart tracings that are worrisome are typically further evaluated with tests including a fetal ultrasound which can estimate the amount of amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus.

The comadronas working with Wuku’ Kawoq also take blood pressure measurements during prenatal visits, which can help to detect gestational hypertension, which occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy in women who have normal blood pressure before this time, as well as pre-eclampsia of which one of the criteria for diagnosis is arterial hypertension after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

Many, though not all, comadronas in my site have a limited ability to read and write, due to many not having progressed beyond a second or third grade education, however, they all have a passion for their job and are first-responders who are quite often present during the birthing process for pregnant women in rural areas of Guatemala. One benefit for utilizing comadronas to take blood pressure measurements, and even fetal heart rate measurements, is to better integrate them into Guatemala’s healthcare system, a goal of the newly instituted “MIS” or Inclusive Health Model in English.

While my health center holds monthly comadrona educational classes, which are given in the local native dialect of K’iche, and while comadronas are encouraged to report pregnancies to the health center, pregnant patients can and do fall through the cracks.

Most of the maternal deaths I am familiar with occurred with pregnant women who were not connected to the local health care system, and sought medical care far too late in an emergency, or the health care system in place could not respond quickly enough. The reason why maternal mortality has decreased little in Guatemala over the past decades, and why decades of educational classes for comadronas may not have improved maternal mortality much, may be less a problem with comadrona training (though classes taught respectfully to the comadrona in her native Mayan language are important), and more an issue of the local health care system, and community, being able to respond quickly enough to get a pregnant woman to a hospital that can handle an obstetric emergency, should the need arise.

I think that giving comadronas a specific task within the healthcare system, such as reporting blood pressure measurements via photos of machine readings, will help to facilitate communication, and a further step might be to select a couple comadronas, for example two comadronas from the roughly fifteen comadronas serving my health district, who could serve as comadrona leaders who could receive additional western medicine training, and perhaps a salary similar to auxiliary nurses at the health center, but whom could also check-in on their fellow comadrona colleagues and help them monitor their patients and serve as a point of contact in the case of an emergency.

If such a comadrona leader could “round” on all of the pregnant women in a given month in my community (about 14), with these women’s comadronas, if available, and complete prenatal visits jointly, this might do much to improve pregnant women’s confidence in the ability of her community to respond in the case of an emergency during her pregnancy as she would know who exactly she would need to call in an emergency.

While auxilary and professional nurses in my health center are aware of comadronas, and help provide monthly educational trainings on topics such as health warning signs during pregnancy and methods of family planning, it is less clear that there are established lanes of communications between the health center and the comadronas. In theory, the local health commissions in a community (one of which I am a member of), should be known to pregnant women and they should be of help with regards to finding a vehicle in a medical emergency if the ambulance is not available, and help to secure emergency funds to get a pregnant women to the hospital in time to save her life if she has a health warning sign, or bleeds too much during delivery. However, a comadrona leader who is well-known to the different communities in my health district, and their health commissions, might be able to serve as a referral point between pregnant women and the local health commission in an emergency as in my experience many pregnant women are unaware of their local health commission, much less how to contact them in an emergency.

Currently, pregnant women suffering an emergency in my health district call a “piloto” or ambulance driver, which may change frequently during the week depending on the day, and the pilotos might not be speciliazed in responding to an obstetric emergency. If my health center could provide cellphones to 2 comadrona leaders, and maybe a professional nurse as back-up who are available 24-7 and known within the community as experts in dealing with pregnant women, this might allow pregnant women to feel more comfortable in calling for help should the need arise, and the comadrona leader might have advanced training in how to more safely transport a pregnant who has postpartum hemorrhage, or who bled too much during delivery and needs to quickly receive intravenous fluids to save her life.

Wuku’ Kawoq, interestingly, has an emergency phone number for their patients, and is answered by a trained health care provider who speaks the local Mayan language, and if their patient then needs to be transported to the local health care center they will then contact the health care center themselves. As there is no 9-11 in Guatemala, the establishment of such emergent referral systems is an area which can be greatly improved upon.

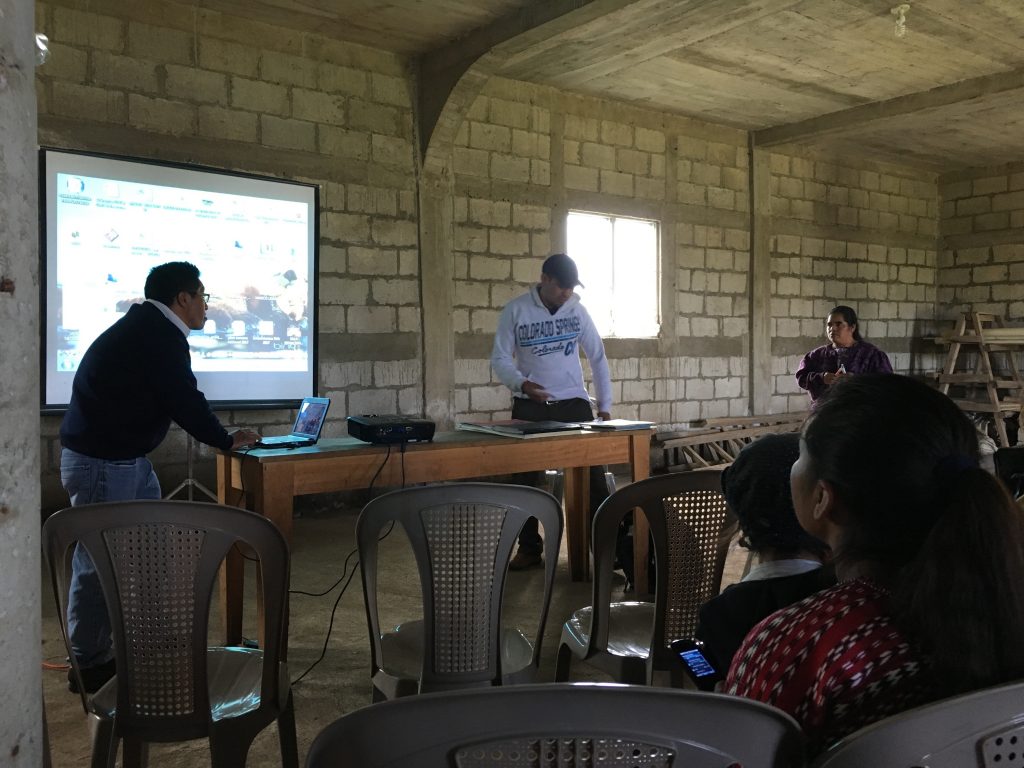

It was great experience being able to present what I learned to my health center, and after hearing about Wuku’ Kawoq cultural sensitive approach to healthcare, the director of my health center has put more emphasis on making sure to communicate in the patient’s native language, and was interested in the Wuku’ Kawoq 9-11 emergency hotline. If there was one cell phone with a permanent emergency hotline for pregnant women, and if this phone was passed between comadrona leaders and professional nurses, it might be possible to maintain a single emergency contact number for many years that is available 24-7 to attend to obstetric emergencies.

If I had the time, and a large grant, it would be interesting to setup a comadrona leader program in my health center where 1 or 2 comadronas could spend time in the health center taking blood pressure, learning about how prenatal checks are done, and being taught to visit pregnant patients with comadronas in the field, while also integrating themselves into the health center’s staff.

4,294 total views, 2 views today

Comments by Mateo

Peace Corps Guatemala: Daily Activities 3: Women’s Group Handwashing Charla

Hi Emilio, I like your blog! I will send a postcard to ...